When I invented Kitty Litter in 1947, being an overbearing boss was the last thing on my mind. Quite simply, there was nobody to boss around. Employees weren’t even a pipe dream back then — I was often using the proceeds of a sale during the day to pay for my hotel room that night. From bagging the clay to changing countless litter boxes at pet shows to demonstrate my product’s prowess, I did it all myself. It would have been great to have help — especially for the litter boxes!

The good news is that by having to do everything, I quickly received a crash course in surviving — and eventually prospering — in the pet-supply business. This, of course, is pretty typical for most people who can’t reach into their back pockets for a few million or so in startup funds. On a scale of self-sufficiency, I’d rank the American entrepreneur right up there with the mountain men of the 19th century.

People power

But if our dreams come true, we grow to the point where there simply aren’t enough hours in a day to run every aspect of our businesses. Though one side of me was only too eager to roll out the welcome mat for help, another side felt like a father watching his daughter leave on her first date. Kitty Litter was my baby, and I didn’t trust just anyone in the nursery.

It helped that the first people I hired filled the needs I was least suited for. My first office manager, Mrs. Egmer (nobody dared call her by her first name), had the demeanor of a drill sergeant, but her attention to everyday details kept our corporate cat box from overflowing in a way that I never could. Another pillar of strength was Jack Rand, a geologist from Maine who I hired to help find deposits of clay for our ever-growing needs. Why I thought that someone from Maine would know much about finding a type of clay native to the Mississippi River valley is beyond me, but I had a hunch about Jack. The hunch found pay dirt time and time again, as Jack helped us cost-effectively obtain the Fuller’s Earth we needed for our hungry plants.

Leveling the playing field

Of course, hunches can also go astray. I hired a popular local fellow as my first sales manager. At work he displayed a side few people knew about — a dark moodiness when he didn’t get his way. Once, after three days under his black cloud, I invited him to unload his feelings. He proclaimed that he was undervalued, and that he wanted 25% ownership of my company. Otherwise, he was going to start his own competitive business. Although he was a pretty decent sales manager, I wished him luck and told him to clean out his desk.

The fact that he was someone I knew well didn’t make it any easier. It taught me the first of many important lessons about hiring friends and others close to you. Evaluate them with the same brutal honesty as any other prospect, or you’re asking for trouble. A growing entrepreneur can’t afford one stick of dead wood.

But when you find the right people, let them do their job. A boss who constantly badgers and second-guesses good employees is as unsettling as a waiter hovering over your every bite in a fine restaurant. Empower your employees; and though you don’t need to dish out slices of your company, pay them well for a good job. As an advertisement once noted, a good mind is a terrible thing to waste — or worse yet, to send running to a competitor.

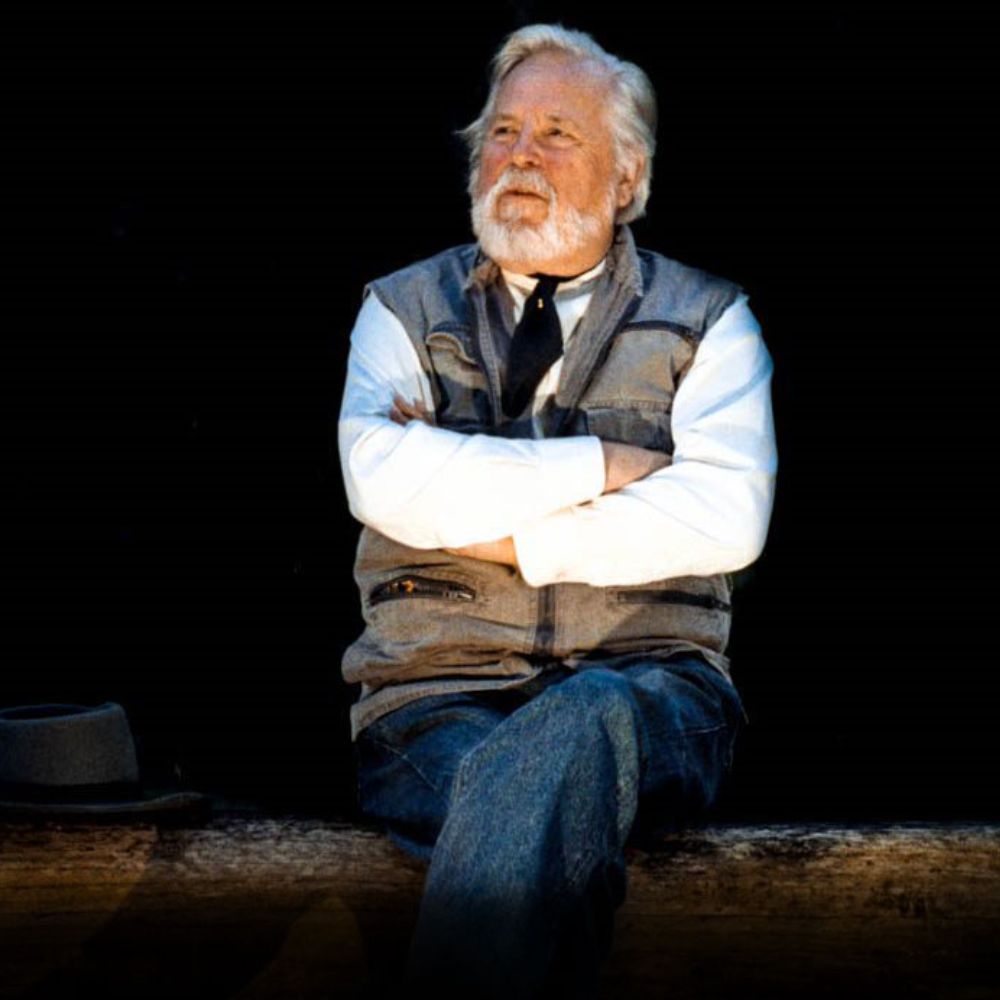

This column is one in a series that will explore the thoughts, ideas and unadorned advice of an entrepreneur who made it, Edward Lowe. When he “brought the cat indoors” with a revolutionary cat-box filler, Kitty Litter, he created an industry that changed the lives of millions of cat lovers, not to mention cats. During his life, Ed Lowe used “plain talk” to speak about the bottom line from the bottom of his heart. We believe these writings, revised and updated after his death, offer value not only for your business but also for your entrepreneurial soul.