This rule came from my Grandpa Huber. Actually, it was part of a trio of warnings he gave me, including, “Never eat at a restaurant named ‘Mom’s,’ ” and “Never play cards with a guy named Ace.” These last two rules are easy to understand, but I never fully comprehended the first one until I bought Jones. Jones is a little town in south Michigan I used to visit as an ice peddler with my father in the 1930s. In 1970 I pulled off the main highway to check it out. I was saddened by what I saw. What I remembered as classic small-town Americana had fallen into time’s dumpster. The population, never large, had shrunk to 200 at most. Only three of the 14 buildings on Main Street were occupied. Even the spiders had vacated.

Walking cracked sidewalks, I peered into empty storefronts and pondered what became of this once-cheerful crossroads town.

Then I got the Big Idea. I would buy Jones and restore it. Not just whitewash the burg and hose down the streets, but return the town to its heyday. I would create a theme village: “Everybody’s Old Home Town.” It would delight tourists, revive the local economy, and provide me the satisfaction of doing something for this dying hamlet, while having a heck of a good time. How could I lose?

On a tangent

The real-estate prices provided even more incentive. In no time I owned most of the land within three blocks of Main Street. The fire-sale prices helped me justify about $1 million I put into the buildings. The Red Garter Saloon was open all day, and at night the Jones Opera House literally buzzed with an old-time melodrama where the villain tries to saw the heroine in half. We had a 19th Century print shop, sawmill, glass blower, gunsmith, even an old haunted house stocked with spooks. If that wasn’t enough, there was a horse-drawn stagecoach, even a hot-air balloon to ride. Re-creating Jones was as fun as anything I’ve ever done.

The problem was, I hadn’t considered the feelings of others critical to its success. Far from rolling out the welcome mat, the residents of Jones — those who were left — resented Ed Lowe bringing in a brass band and a passel of strangers to transform their lifelong home into a Midwestern Disneyland. They hated the slogan, “Jones is Back!” because their Jones never left — until I came along.

My corporate family was equally annoyed. I was spending about 90% of my time on the project, at the expense of the company I should have been minding. They also considered the money a frivolous expense better used for bonuses, retirement funds, almost anything.

An expensive lesson

With neither of these two critical elements on my side, I knew that Jones would never become a tourist magnet. Even if it had been, I didn’t want to pay the price. I sold all my holdings at auction at a big loss. But I learned something that was probably worth the money.

Entrepreneurs are full of ideas and energy; that’s why we often succeed against the odds. But we have to realize that unless our key allies buy into our dreams, they can become nightmares. Whether it’s distributors, financiers or your employees — especially your employees — the people critical to your success must support you before diving headfirst into a new direction. Use your personal time and money — not your company’s — for pet projects.

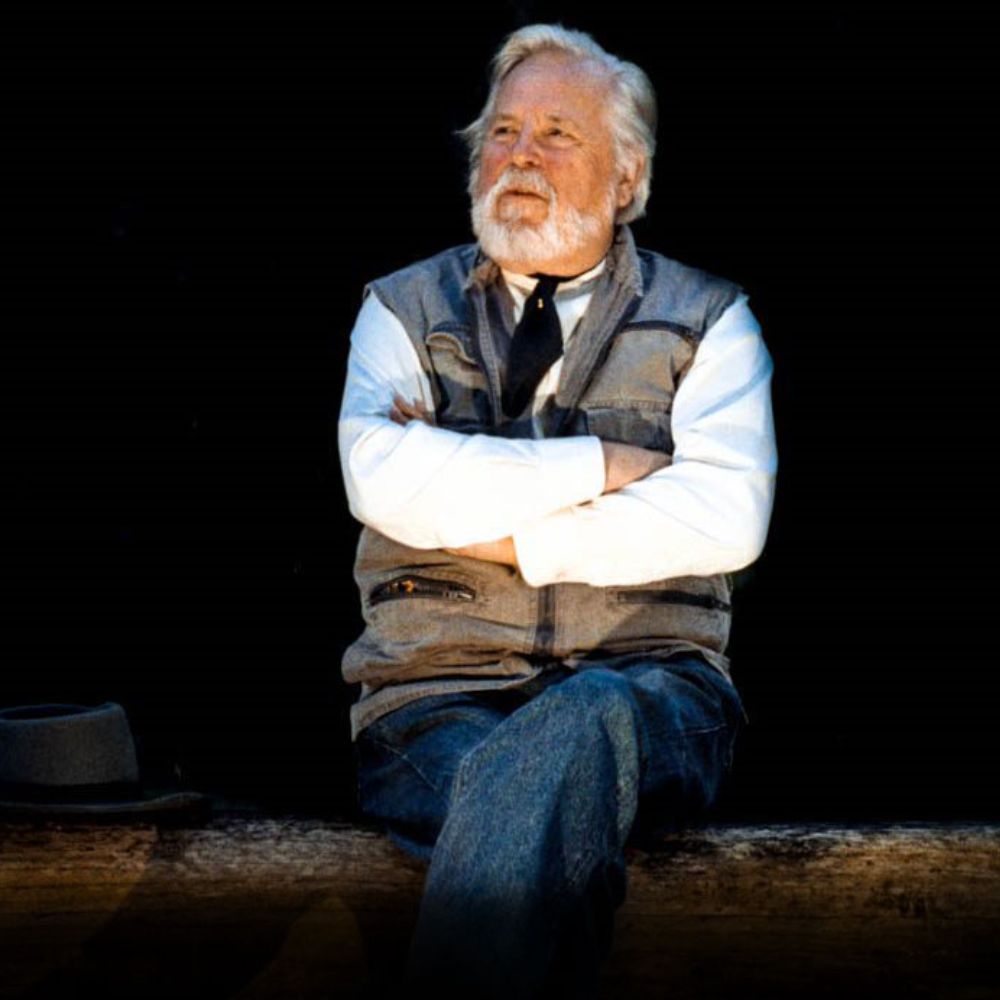

This column is one in a series that will explore the thoughts, ideas and unadorned advice of an entrepreneur who made it, Edward Lowe. When he “brought the cat indoors” with a revolutionary cat-box filler, Kitty Litter, he created an industry that changed the lives of millions of cat lovers, not to mention cats. During his life, Ed Lowe used “plain talk” to speak about the bottom line from the bottom of his heart. We believe these writings, revised and updated after his death, offer value not only for your business but also your personal life